Why the Internet Gets This One Wrong — and Why Precision Can Save Your Life

Understanding a widely misused term—and what your relationship actually needs

You see it everywhere now—social media posts, podcast discussions, conversations with friends. Someone had a difficult breakup, and suddenly: "I was trauma bonded." A coworker stays in an unfulfilling job: "Must be trauma bonding." A friend tolerates rude behavior from family: "That's trauma bonding, right?"

The term has become cultural shorthand for "I stayed when I should have left." And while the widespread recognition of this concept represents important progress in understanding abusive relationships, something valuable gets lost when clinical terms become catch-all explanations for every disappointing relationship dynamic.

Let's talk about what trauma bonding actually is—and what it isn't.

What Trauma Bonding Actually Means

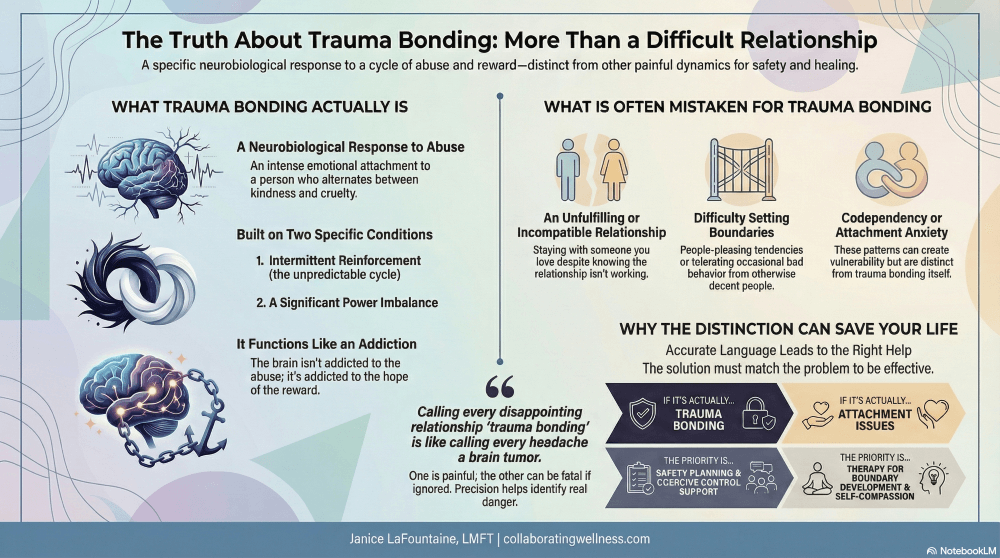

Trauma bonding is a specific psychological phenomenon where someone develops an intense emotional attachment to a person who engages in a pattern of intermittent abuse and reward. This isn't simply staying in a bad relationship or having difficulty leaving someone who treats you poorly. It's a predictable neurobiological response to two specific conditions: intermittent reinforcement (unpredictable switching between kindness and cruelty) and a significant power differential.

Think of it this way: Your brain isn't "bonded" because someone is consistently terrible to you. In fact, if someone were awful 100% of the time, leaving would be straightforward. The trap of trauma bonding comes from the unpredictable cycling—periods of intense affection and connection followed by devaluation and abuse, then back to affection again. This pattern hijacks the brain's reward system, creating something that functions remarkably similar to addiction.

The architecture of this bond is built through specific tactics: love bombing that creates profound initial connection, gaslighting that undermines your trust in your own reality, isolation from support systems, and systematic destruction of your autonomy. These aren't just "relationship problems"—they're deliberate patterns designed to create dependency.

The Neuroscience Behind the Bond

Here's where it gets both fascinating and heartbreaking. When you're in a trauma-bonded relationship, your brain's dopamine system (the seeking and wanting system) becomes hyperactivated by the intermittent reward pattern. You're not addicted to the abuse—you're addicted to the hope of the reward, the return of that initial connection. Meanwhile, your bonding system (driven by oxytocin and endogenous opioids) ensures that any attempt to leave triggers genuine withdrawal symptoms: grief, anxiety, and overwhelming psychological pain.

The constant stress of the abusive environment amplifies these systems rather than weakening them. The highs feel more euphoric, the pain of separation becomes more intense and unbearable. This is neurochemistry, not weakness.

What Gets Misidentified as Trauma Bonding

Now let's talk about what trauma bonding isn't:

Trauma bonding is not:

- Staying in a relationship that's unfulfilling but not abusive

- Finding it hard to leave someone you genuinely love despite incompatibility

- Tolerating occasional bad behavior from otherwise decent people

- Having complicated feelings about family members who hurt you without systematic manipulation

- Difficulty setting boundaries due to people-pleasing tendencies

- Codependency (though codependent patterns can make you more vulnerable to trauma bonding)

These experiences are real and valid. They deserve attention and often require therapeutic support. But calling everything "trauma bonding" dilutes our ability to recognize the specific, dangerous dynamics the term was created to describe.

Why the Distinction Matters

"Calling a disappointing relationship 'trauma bonding' is like calling every headache a brain tumor. Both hurt. Only one is usually fatal if ignored."

When we use "trauma bonding" as a catch-all for "any relationship I found hard to leave," several things happen:

For people in actual abusive relationships: The dilution makes it harder for them to recognize the specific danger they're in. Trauma bonding isn't just emotionally difficult—it's a marker of systematic psychological abuse that often escalates. When the term loses its clinical precision, survivors miss the warning signs that should trigger safety planning.

For people working through difficult but non-abusive relationships: Mislabeling creates unnecessary fear and confusion. You might be dealing with attachment anxiety, poor boundaries, or grief about ending something that wasn't working—all of which need addressing, but not through the lens of abuse recovery.

For understanding your own patterns: Accurate language helps you access the right resources. If you're actually dealing with attachment wounds from childhood or codependent patterns, trauma bonding resources won't address the core issue. You need different tools.

How to Recognize Actual Trauma Bonding

True trauma bonding unfolds in recognizable stages: It begins with love bombing (intense idealization and boundary-testing), progresses to building trust and dependency, then introduces criticism, gaslighting, and control. Eventually, you experience resignation and loss of self, culminating in an addiction-like attachment where you crave the return of the initial "high" despite enduring ongoing devaluation.

Ask yourself these questions:

- Does this person use unpredictable patterns of reward and punishment to keep you off-balance?

- Do you find yourself questioning your own perception of reality because they consistently deny or distort events?

- Have you become isolated from friends and family, either through direct prohibition or because maintaining those relationships creates so much conflict it's not worth it?

- Do you feel you've lost touch with your own needs, feelings, and identity?

- Is there a significant power differential where you feel genuinely fearful of their reaction?

- Do you experience cognitive dissonance—the painful mental state of simultaneously believing "this person hurts me" and "this person loves me"—and find yourself minimizing or rationalizing the abuse to resolve this discomfort?

If you answered yes to most of these, you may be experiencing actual trauma bonding, and your situation requires specific safety-focused interventions.

What to Do If It's Not Trauma Bonding

If you're struggling to leave a relationship but the pattern doesn't match trauma bonding, you're not "making it up" or being dramatic. You might be dealing with:

Attachment anxiety from early relationships that makes separation feel intolerable even when someone isn't right for you. This is real neurobiology—just different neurobiology than trauma bonding.

Grief and loss about a relationship ending, even when ending it is the right choice. You can love someone and simultaneously recognize that staying together doesn't work.

Boundary challenges rooted in childhood experiences where your needs weren't prioritized. You learned to override your own compass, and that's a pattern that requires healing.

Genuine love combined with incompatibility or different life directions. Sometimes relationships end not because someone is abusive but because love alone isn't enough.

All of these deserve compassionate attention and therapeutic support. None of them are trauma bonding.

Getting the Right Support

Understanding what you're actually dealing with matters because it points you toward the right help:

If you're in a trauma-bonded relationship: Your first priority is safety planning, not relationship repair. You need support from professionals trained in domestic violence and coercive control who understand that the most dangerous time is when you leave.

If you're struggling with attachment patterns or boundaries: Individual therapy focused on attachment repair, self-compassion, and boundary development will serve you better than trauma-bonding frameworks.

If you're grieving a relationship that ended: Allow yourself to grieve without pathologizing the attachment. Sometimes the hardest part of leaving isn't that you were bonded through abuse—it's that you loved someone you couldn't stay with.

The Value of Precision

Language shapes how we understand our experiences and access help. When we use clinical terms precisely, we honor both the severity of what they describe and the full range of human struggle they don't capture.

You don't need to have been "trauma bonded" for your pain to be real or your difficulty leaving to be valid. But if you were trauma bonded, recognizing that specific pattern could save your life.

If these patterns sound familiar and you're in Spokane or Idaho: I specialize in trauma recovery and coercive control, including trauma bonding and its aftermath. Whether you need help understanding what you experienced or support rebuilding after leaving, therapy can help you reclaim your sense of self and reality.