Unpacking pop psychology's obsession with the term—and what's actually happening clinically

Open any social media app and scroll for a few minutes. You'll encounter content about narcissists: how to spot them, how to leave them, how to heal from them. The term has become cultural shorthand for anyone who's selfish, manipulative, or emotionally unavailable. Your difficult ex? Narcissist. Your controlling parent? Narcissist. Your self-absorbed coworker? Definitely a narcissist.

This linguistic explosion reflects something real and important—people are trying to name experiences of profound mistreatment and manipulation that often went unacknowledged by therapists, family members, and society at large. The word gives form to experiences that were previously dismissed with "that's just how they are" or "you're being too sensitive." For many people, discovering the term "narcissist" was the first time someone validated what they'd been living through.

But the mainstreaming of a clinical term has also created complications. When everyone who hurts us becomes a narcissist, we may be obscuring more than we illuminate—both about these difficult people and about what actually helps us heal from the damage they cause. Let's unpack this together.

The Clinical Reality: What Narcissistic Personality Disorder Actually Means

In clinical settings, Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) is a specific diagnosis with defined criteria—not just a description of someone who's hard to deal with. The DSM-5 identifies NPD as a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, need for admiration, and lack of empathy, indicated by five or more of the following:

DSM-5 Criteria for NPD:

- A grandiose sense of self-importance, often exaggerating achievements and talents

- Preoccupation with fantasies of unlimited success, power, brilliance, beauty, or ideal love

- Belief in being "special" and unique, only understood by or able to associate with high-status people or institutions

- Requiring excessive admiration

- A sense of entitlement—unreasonable expectations of especially favorable treatment

- Being interpersonally exploitative, taking advantage of others to achieve personal ends

- Lacking empathy—unwilling to recognize or identify with the feelings and needs of others

- Often envious of others or believing others are envious of them

- Showing arrogant, haughty behaviors or attitudes

What the criteria don't fully capture is the variability of how these patterns present in real life. Contemporary clinical thinking recognizes that narcissism involves a vulnerable and variable self-esteem, with desperate attempts at regulation through approval-seeking and either overt or covert grandiosity. It's not always the loud, bragging type you see in movies.

The impairment shows up in four domains: identity (excessive reliance on others for self-definition and self-esteem regulation), self-direction (goal-setting based on gaining external approval rather than internal values), empathy (impaired ability to recognize others' feelings and needs, or attunement that only activates when relevant to oneself), and intimacy (relationships that remain superficial and serve self-esteem regulation rather than genuine connection).

Importantly, NPD exists on a continuum. Some presentations are relatively benign—difficult but not destructive. Others shade into what clinicians call malignant narcissism, involving exploitation, paranoia, sadism, and Machiavellian manipulation. The same diagnostic label covers a wide range of severity, which is part of what makes the term so confusing when it's used casually.

Beyond the Monolith: Different Presentations of Narcissistic Patterns

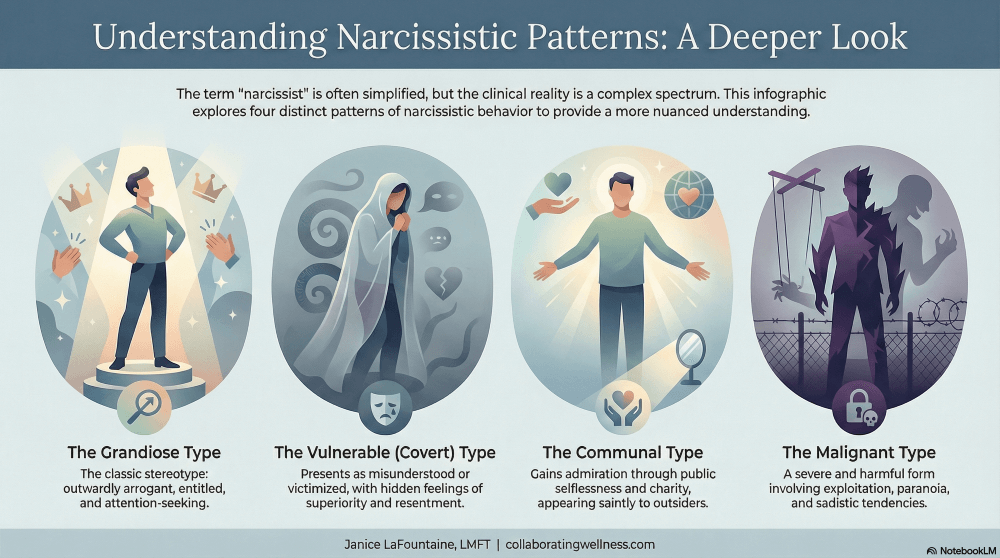

One of the biggest problems with the popular discourse is that it tends to imagine narcissists as a single type—usually the grandiose, bragging, obviously self-important variety. Clinical observation reveals far more complexity, and understanding these differences can help you make sense of your own experiences.

Grandiose Narcissism: This is the prototypical presentation—what most people picture when they hear the word. Grandiose narcissists display guileless braggadocio, attention-seeking, contempt for others they deem beneath them, entitlement, and often boredom with ordinary life. They're the "disagreeable extravert"—their narcissism is visible, even flamboyant. These are often the easiest to spot and the quickest to leave because their behavior is so obviously problematic.

Vulnerable or Covert Narcissism: This presentation often goes completely unrecognized because it doesn't match the stereotype at all. Vulnerable narcissists present with what researchers call "victimized grandiosity"—they believe they're special but misunderstood, overlooked, or persecuted by a world that fails to recognize their worth. Where grandiose narcissists project confidence, vulnerable narcissists present with negative mood states: depression, irritability, social anxiety, resentment. They're the "disagreeable introvert." Their relational style tends toward passive-aggression, petulance, and sullenness rather than overt domination. If you've been confused because your difficult person doesn't match the stereotype, this might be why.

Some clinicians use the term "fragile tyrant" to capture how grandiosity and vulnerability exist together—the same person can oscillate between "I'm the king of the world" and "the world doesn't see that I should be the king of the world." Both states are equally controlling.

Communal Narcissism: These individuals meet their needs for admiration through "helping others." They anticipate public reverence for their selflessness, expect recognition and awe for their charitable works, and often present a saintly public face that differs markedly from their private conduct. Partners and family members of communal narcissists often struggle with intense cognitive dissonance—reconciling the person everyone else sees as generous and giving with the controlling, entitled person they experience at home. This type can be particularly crazy-making because no one believes you when you describe what's actually happening.

Malignant Narcissism: At the severe end of the spectrum, malignant narcissism involves exploitation, antagonism, paranoia, and sadistic pleasure in others' suffering. These individuals engage in complex rationalizations for their behavior and rarely accept genuine responsibility or show authentic contrition. Malignant narcissism overlaps with what researchers call the "Dark Triad" (narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy) or "Dark Tetrad" (adding sadism). These are the individuals who cause the most severe harm in relationships and are least likely to change—frankly, they don't want to change because the current arrangement serves them perfectly.

What Creates Narcissistic Patterns?

Understanding the origins of narcissism doesn't excuse harmful behavior—that's crucial to remember—but it can provide context for why these patterns are so resistant to change. Researchers have identified multiple developmental pathways:

Attachment-based narcissism develops when early caregiving fails to provide secure attachment, leaving the child with an unstable sense of self that requires constant external validation. The person never developed an internal sense of worth, so they're always seeking it from outside.

Post-traumatic narcissism can emerge as a protective adaptation to early trauma—grandiosity as armor against overwhelming vulnerability. "I can't be hurt if I'm special and superior."

"Performing-pony" narcissism develops when a child's worth is tied entirely to achievement and external performance, creating an identity built on accomplishment rather than inherent value. Love was conditional on success, so the adult can't separate their worth from their achievements.

Mirrored narcissism occurs when parents use the child as an extension of themselves, rewarding the child for reflecting the parent's desired image rather than developing their own authentic self. The child learns that their own preferences and identity don't matter—only the parent's vision of who they should be.

Enabled or cultural narcissism develops when family systems or cultural contexts consistently reinforce entitled, exploitative behavior without consequence. The person learns that other people exist to meet their needs.

The common threads include over- or under-indulgence, modeling of difficult behavior, and conditional worth—the message that love and belonging depend on performance, achievement, or meeting the parent's needs. These origins can evoke compassion, but they don't obligate you to tolerate harm.

The Nomenclature Problem: When Clinical Terms Go Mainstream

Here's where the clinical and popular uses of "narcissist" start to diverge in ways that actually matter to your recovery.

The Risk of "Medicalizing Meanness": Because the term "narcissism" is clinical, its popular use risks "medicalizing" meanness—turning bad behavior into a mental health diagnosis. When we call someone a narcissist, we're implicitly suggesting they have a diagnosable condition—and that can create real complications.

It may seem to excuse the behavior ("he can't help it, he has NPD") or imply that it's something that can be "worked through" in therapy. I need to be honest with you: the treatment literature for narcissistic personality patterns is not encouraging on this front. Unlike depression or anxiety, where therapy typically helps significantly, personality disorders are notoriously difficult to treat, and narcissistic presentations are among the most challenging because the person typically doesn't see a problem with themselves. They're not seeking change—they're seeking validation that they're right.

Using a diagnostic term can also pathologize you by implication—if your partner has a "disorder," then you're the one married to someone with a mental illness, which can complicate the moral clarity you need to leave. It can make leaving feel like abandoning someone who's sick rather than protecting yourself from ongoing harm.

What We're Actually Describing

When most people use "narcissist" in everyday conversation, they're not really trying to make a clinical diagnosis. They're describing a cluster of experiences: being manipulated, exploited, devalued, gaslit, controlled, or treated as an extension of someone else rather than as a separate person with valid needs. The label is a shorthand for "this person hurt me in ways that are hard to explain."

Some clinicians have proposed alternative frameworks that focus on the relational harm rather than the (undiagnosed) internal pathology of the difficult person. These can be incredibly helpful:

Antagonistic Relational Stress (ARS) captures the territory most people mean when they talk about "narcissistic abuse"—manipulation, exploitation, dysregulation, entitlement, and lack of empathy—without requiring an armchair diagnosis. It describes what's happening in the relationship rather than labeling the other person's mental health. This can be much more useful therapeutically.

The CRAVED framework characterizes antagonistic personalities as Conflictual, Rigid, Antagonistic, Vulnerable, Entitled and Egocentric, and Dysregulated—descriptive terms that don't require assuming a specific clinical diagnosis. You can describe behavior patterns without claiming to know what's happening in someone's psyche.

Emotional immaturity offers another lens. From this perspective, narcissistic behaviors represent developmental arrests—the person is operating from the emotional toolkit of a much younger self. They share core issues with all emotionally immature people: attachment disruption, unstable sense of self, and attempts to fix internal problems through controlling others. Sometimes thinking of them as emotionally stuck at age seven can help you stop expecting adult responses.

Each framework has value. The diagnostic model provides clinical precision. The relational harm frameworks validate your experience without requiring you to diagnose someone else. The developmental lens can help with compassion (though compassion should never mean tolerating abuse). Use whichever framework helps you understand your experience and move forward.

Why the Mental Health Field Has Struggled With This

Many survivors of manipulative, exploitative relationships have found the mental health system unhelpful—sometimes even actively harmful. If this has been your experience, you're not alone, and your frustration is justified.

Part of this reflects legitimate therapeutic concerns. Therapists are trained not to diagnose people who aren't in the room, and focusing on someone else's pathology can sometimes be a way of avoiding your own work. "Why did I stay?" is generally a more therapeutically productive question than "What's wrong with him?"

But this appropriate caution has sometimes led to real failures. Practitioners may avoid discussing the difficult person outside the room entirely, leaving you without language for your experience. They may inadvertently pathologize you—treating your trauma responses as the problem rather than the traumatic relationship itself. Many therapists lack adequate training in high-conflict personality patterns and the specific dynamics of coercive control. They mean well, but they simply don't know what they're looking at.

When someone has been systematically gaslit, having a therapist who won't validate that the other person's behavior was abusive can feel like a continuation of the gaslighting. Your reality gets questioned yet again, this time by someone you're supposed to trust for help.

The Distinction Between Narcissism and High Self-Esteem

One clarification worth making, especially if you've been accused of being "too confident" or told you're the narcissistic one: narcissistic grandiosity is not at all the same as healthy self-esteem.

Genuine high self-esteem is associated with wellbeing, optimism, life satisfaction, and low hostility. It's stable—it doesn't require constant external validation and doesn't collapse under criticism. Someone with healthy self-esteem can hear negative feedback without their entire sense of self crumbling.

Narcissistic grandiosity, by contrast, is fragile and requires constant feeding. It's associated with hostility, defensiveness, and devaluation of others. The grandiose presentation masks underlying insecurity rather than reflecting genuine self-worth. Any perceived criticism becomes a threat requiring immediate defense or counterattack.

This distinction matters because it clarifies that the problem isn't someone thinking well of themselves—it's the compensatory, unstable, and interpersonally destructive nature of narcissistic self-inflation. Healthy confidence lifts everyone up. Narcissistic grandiosity requires putting others down.

What This Means for Those Who've Been Harmed

If you recognize your experience in descriptions of narcissistic relationships, a few considerations may genuinely help you move forward:

You don't need a diagnosis to validate your experience. Whether or not your difficult person meets criteria for NPD, the impact on you is real and deserving of attention. You don't need to prove they have a personality disorder to justify your pain or your decision to create distance. Your experience of harm is enough.

Focus on behaviors and impacts, not labels. "He systematically undermined my perception of reality" is more useful than "he's a narcissist." It describes what happened to you rather than making a claim about his psychology that you can't prove and don't need to prove.

Be wary of over-identification. While psychoeducation about narcissistic patterns can be validating and genuinely illuminating, there's a real risk of the "narcissist" framework becoming an all-consuming lens that keeps you focused on the other person rather than your own recovery. At some point, you need to shift from understanding them to reclaiming yourself.

Understand that explanations aren't excuses. Understanding that someone's narcissistic patterns may stem from their own developmental trauma doesn't obligate you to tolerate their behavior. You can feel compassion for someone's wounds while maintaining firm boundaries against their harmful behavior. Both things can coexist, and you're not a bad person for protecting yourself.

Seek therapists who understand these dynamics. Not all therapists are trained in coercive control, manipulative relationships, or the specific dynamics of antagonistic personality patterns. A therapist who truly understands these territories can provide appropriate validation while also supporting your work on healing and moving forward. Trust your instincts—if a therapist makes you feel like you're overreacting or being unfair, that's important information.

Moving Forward

The explosion of "narcissist" in popular culture reflects a real and important need—people trying to name and make sense of experiences of manipulation, exploitation, and devaluation that were often minimized or completely ignored. For many, it was the first language they had for something that had been eroding them for years.

The clinical reality is more nuanced than the pop psychology version. Narcissism exists on a spectrum, presents in different forms, develops through various pathways, and may be better understood through frameworks that emphasize relational harm rather than diagnostic labels. But this nuance doesn't diminish the validity of what you've experienced.

What remains constant is that relationships with antagonistic, entitled, empathy-impaired individuals cause genuine damage—to self-esteem, to reality-testing, to the capacity for trust. Recovery involves reclaiming your perception, rebuilding your sense of self, and developing the discernment to recognize these patterns earlier in the future. This work is real, it matters, and you deserve support in doing it.

Whether you call that experience "narcissistic abuse," "antagonistic relational stress," or something else entirely, your task is the same: to heal, to rebuild, and to create relationships that honor your full humanity. You're not being dramatic. You're not overreacting. And you're absolutely not alone.

If these patterns sound familiar and you're in Washington or Idaho: I specialize in trauma recovery and coercive control, including recovery from narcissistic and antagonistic relationships. Whether you need help understanding what you experienced or support rebuilding after leaving, therapy can help you reclaim your sense of self and reality. You don't have to figure this out alone.